Digital documentation, architecture, community and open source knowledge.

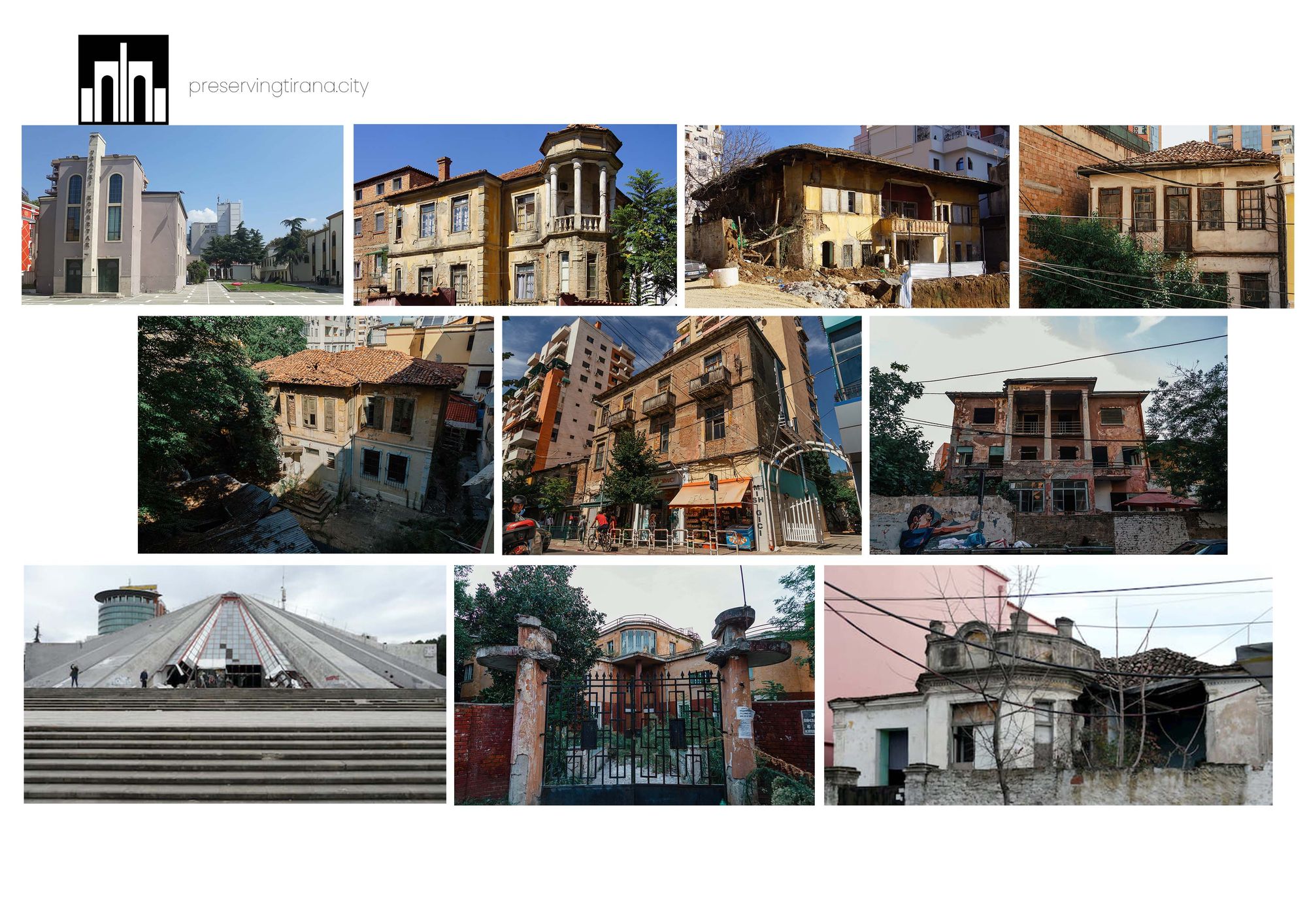

While there were a number of catalysts behind Preserving Tirana, the existing urban situation in the city of Tirana itself was undoubtedly the chief one among them. The lived complexity of the city of Tirana as we know her today belies her age. Even though it is not one of the oldest cities in Albania, however Tirana’s journey has been marked by a process of rich historical layering in time which is clearly reflected in its architecture and urban fabric more generally. The year 1614 marks the creation of the first urban nucleus in Tirana around the mosque of Sulejman Pasha, a bakery, and the shrine of Kapllan Pasha. Throughout the period of Ottoman occupation Tirana developed in a mostly organic way. This lasted until the years of the Italian protectorate and fascist occupation (1925–1944), a period of intense architectural and urban planning developments in Tirana. During the communist dictatorship (1945–1990), Tirana’s architecture and urban planning were dominated by the Soviet style and the Albanian socialist realist style.[2] The postsocialist period beginning in 1990, by virtue of being characterized as a transitional period, has been defined in architectural terms by chaotic and uncontrollable urban development. It is extremely important that for the sake of maintaining this continuity in time which is materialized, among other things, in architectural works, the key buildings representative of these periods are identified and preserved. Due to the absence of preservation efforts and processes, such as restoration, conservation, etc., these architectural works exist today in a state of limbo, in spite of their considerable architectural, cultural, and historical capital for the city, leading to them being ironically baptized as Tirana’s “undesirable buildings”. Their mere existence was the first catalyst for starting this project.

The participation in a research workshop on the urban organized by the Institute of Cultural Anthropology and the Study of Art created a productive environment in terms of allowing us to further elaborate this idea. In addition, being exposed to Dutch anthropologist Melanie Van der Hort’s book Indispensable Eyesores: An Anthropology of Undesired Buildings, helped us look at the problem from a wider perspective in terms of its broader geographical and historical context. We started to think about concepts such as the value of an architectural work, the power of determining that value, and how that value can easily change depending on the interest group that attributes it. This made me want to tackle the question of the abandoned and undesirable architecture of post-communist countries in Eastern Europe in the context of Tirana and its abandoned, undesirable buildings which were becoming increasingly discernible to our eyes and whose predicament seemed increasingly alarming to me. Interestingly, Van der Horn posits the existence of a hypothetical axis for determining the value of architectural works. On either end of this axis are located the buildings that have a positive or a negative value attached to them; in the middle of the axis are located the buildings that have a value of “0” attached to them, in other words buildings that the community is indifferent towards; while anything between these three points represents a grey area in which are included a vast array of buildings. The category of buildings that have a positive value attached to them includes buildings that are deemed to be valuable from an institutional point of view, listed buildings, buildings that are included in architecture books, tourist guides etc. The buildings anchored to the negative pole on the axis are typically buildings that are associated with a grim historical event that occurred at a given point in the past.[3]

In this way, one begins to understand how the value that is attributed to a building depends on the interest group that bestows it, and that it is subject to change with the passing of time. To begin with, at any given time the same building is valued quite differently by the community, by policy making structures and decision making entities.

Similarly, the same building can shift along the axis from the positive pole to the negative pole and vice-versa at different times and historical periods. There are many examples of this in Tirana, such as the case of the Pyramid (Piramida), Maks Velo’s apartment block featuring a cubed structure (pallati me kuba), with the most sensitive and actual example being that of the “Skёnderbej” Complex and the building of the National Theatre which was “sacrificed”, i.e. demolished. Buildings such as these, which have a very rich life cycle and are witnesses to the most important changes that the country has undergone, be they historical, political, and/or social, must be identified and protected at all costs.

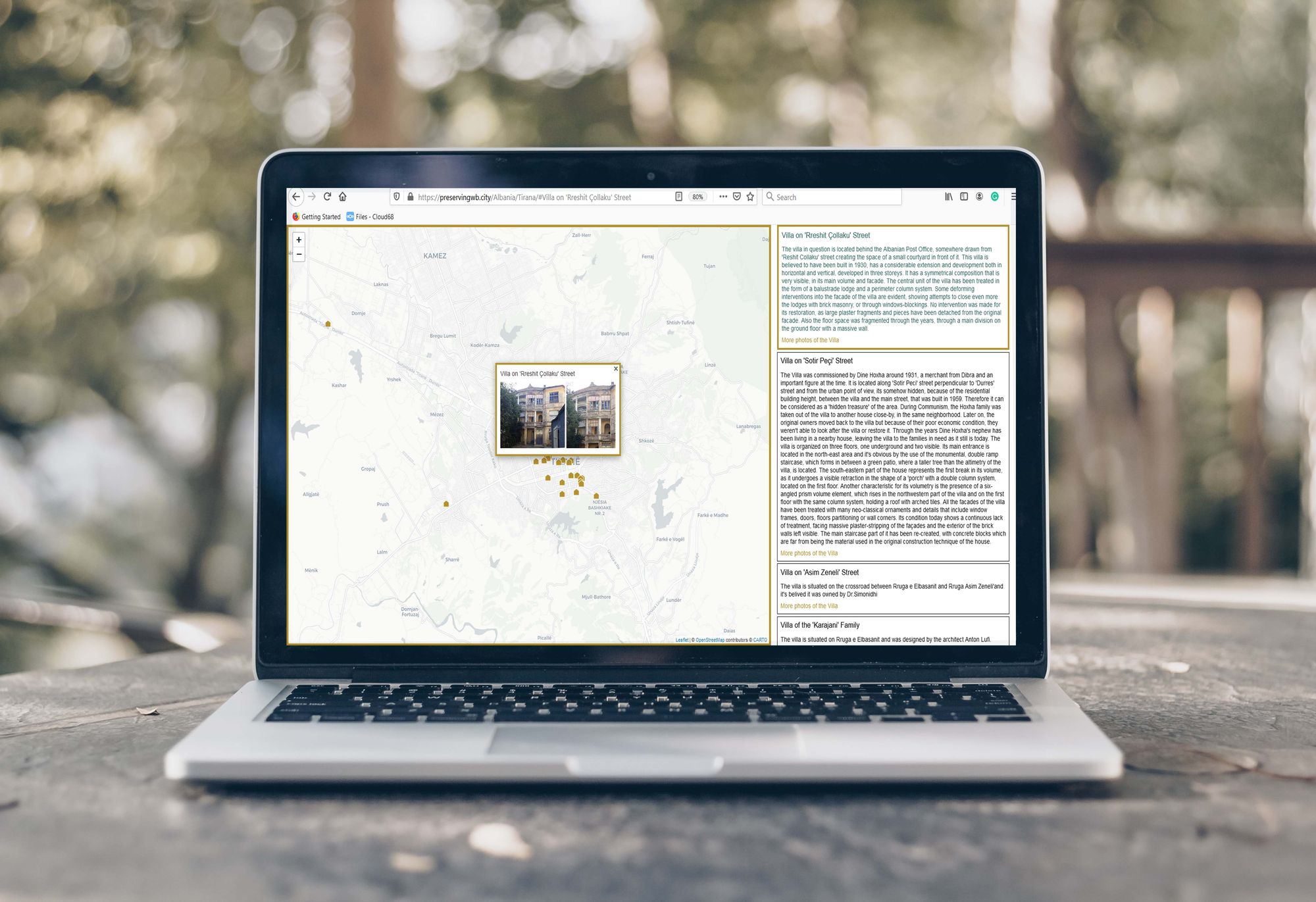

PreservingTirana, or, to be precise, preservingtirana.city was conceived as an interactive platform of digital documentation. The database integrates theoretical architectural research with interviews with the local community living in the vicinity of the buildings documented on the website, and various documentation techniques including in-situ mapping of the buildings documented, their geographic location, and photographic documentation.

This platform makes the preservation of this vulnerable and endangered category a worthwhile pursuit, at a time when the institutional will to do so is lacking, while simultaneously representing a public archive of the historical layering of Tirana in time. (Fig. 1)

The website ensures that there exists in the public domain, which is crucial, a source of concise and structured information about the architecture of Tirana. As a result, this information is rendered more accessible, which it often is not unless one is part of certain professional circles or has access to specialized literature on architecture and the urban, without factoring in the many procedural and bureaucratic difficulties that are routinely encountered when trying to access materials stored in public institutions in Tirana.

Creating a democratic process for the participation of the community in the project, by effectively turning them into active participants in its realization, was a key concern. Since these buildings are a common good that belongs to the city, it follows that the process of gathering information about them and, in turn, feeding this information into the database, is a collective right and responsibility. Unfortunately, however, the concept of the commons is one that has been egregiously abused with throughout modern Albanian history, especially during the communist dictatorship but also now, in the post-communist era. Consequently, attempts to foster a proactive approach toward the preservation of this architectural, spatial, and material common good that is so intimately bound up with our collective identity, can come across as being confusing and challenging.

We are all witnesses to the accelerated rate at which these historical buildings are being demolished at present, making the grim prospect of destruction as the primary means for changing the face of the city a realistic scenario in the not too distant future. Consequently, what this project can do is to at least preserve some of the traces of the authentic Tirana, which, in the current situation, has started to resemble more and more Maurilia, one of Italo Calvino’s cities in Invisible Cities (Le città invisibili):

“Beware of saying to them that sometimes different cities follow one another on the same site and under the same name, born and dying without knowing one another, without communication among themselves. At times even the names of the inhabitants remain the same, and their voices’ accent, and also the features of the faces; but the gods who live beneath names and above places have gone off without a word and outsiders have settled in their place. It is pointless to ask whether the new ones are better or worse than the old, since there is no connection between them, just as the old post cards do not depict Maurilia as it was, but a different city which, by chance, was called Maurilia, like this one.”[4]

Methods of documentation

From the outset, multidisciplinarity is something that was very much at the forefront of our thinking about Preserving Tirana, in the sense that we wanted it to merge architectural research on the one hand and open source culture on the other. Consequently, it was important to us that the platforms used in building preservingtirana.city were open source and representative of ethical tech knowledge. And, indeed, the entire structure of the website and the information contained therein, are under an open creative license, Creative Commons ShareAlike 4.0, which means that everything on the website can be freely accessed and used, be it for profitable or non-profitable ends, as long as the source is clearly and properly cited. In addition, everything is documented and stored on GITHUB, a platform widely used by software developers and not only, to organize team work. Anyone can improve or replicate the structure of the website, for instance, in order to build a similar website for a different city that is facing the same issue, as long as they have some technical knowledge.

Other open source platforms that were used in the project include: Open Street Map in order to locate the geographical position of the buildings on a map that was created by volunteers from a number of different countries, collaboration being a key aspect of open knowledge; Wikimedia Commons, which is Wikipedia’s analogue platform that is intended as a repository for audio, photographic, and video materials, and that has also been built through the contributions of millions of volunteers. The use of this platform in particular, guarantees a double contribution, for the project as well as for Wikimedia itself, by expanding the graphic database on Albanian architecture on this website.

On the subject of the methodology used in this project, it combined theoretical research on architecture literature with fieldwork. Quite often we would start by combing through the existing literature on the architecture and history of Tirana in order to identify buildings of interest, which we would subsequently locate on the ground and map. There were times in which the opposite happened as well, however. Thus, it was not uncommon to discover peculiar architectural features or types of features during our fieldwork, which we would then proceed to gather more information about, primarily of a historical or descriptive nature, by interviewing the local community, and, eventually, by researching the literature.

Being a project that is by nature multidisciplinary and that seeks to engage people of different backgrounds on an ongoing or long-term basis, meant that the process of building a platform that would allow for the input of a multitude of participants with different types of expertise was challenging both on a conceptual and logistical level. While team work is something that, as we know, can boost creativity, it can also be more trying. (Fig. 2)

We also faced many difficulties during fieldwork, especially while interviewing local community members. It was often very difficult to direct the conversation towards the topics that were the most interesting for and relevant to the project. We also encountered a considerable amount of skepticism and an unwillingness to share information, especially in those cases where the building owners confused us with representatives of state or local government institutions, which is what happened, for instance, with the building known as “Sarajet e Toptanёve”. Additionally, many of the buildings we documented and researched were abandoned, with their original owners often living abroad, which made both the buildings and the information about them less accessible. In still other cases, some of these abandoned buildings which had fallen into ruin were occupied by homeless people and squatters who, understandably, viewed us with suspicion when we tried to engage them in conversation about their makeshift dwellings, fearing that we could potentially jeopardize their continued stay inside these buildings, which is what happened in the former residence of Radio Tirana.

Raising awareness within the community about the benefits of using open source platforms and encouraging members of the community to contribute to the website proved challenging as well. As a means of addressing these issues we organized a series of workshops in order to equip people interested in contributing to the website with the skills to do so. We also organized activities such as guided architectural tours of the city in order to drum up support for Tirana’s “undesirable buildings”, in a process that may be described as participatory architecture.

In Albania, the institutional evaluation of architectural works, in other words their listing as monuments of cultural heritage, is a relatively late practice. Since the founding of the Institute of Monuments (today NICH- National Institute of cultural Heritage) in the 1960s and up until now, there have been very few attempts to properly evaluate Albania’s modernist buildings for example, which exposes them to degradation and arbitrary interventions.

Because of the backdrop against which the project was conceived, it was very clear to us that it would have a political dimension. Because of the very category of buildings documented in the project, it was never going to be just about providing informative architectural documentation. The urban context in which the project was conceived, which was a direct consequence of the political context, demanded some kind of reaction, some form of resistance. Obviously, since people tend to use the means and methods at their disposal or, at least, the ones they know best in their resistance efforts, the approach that made most sense for us given our collective skill set, was this participatory architectural platform. As a result of the latter, we have noticed an increased awareness about Tirana’s “undesirable buildings” on the community level, which has been amplified by the reactions on our communication channels as well as through direct contributions on the preservingtirana.city website.

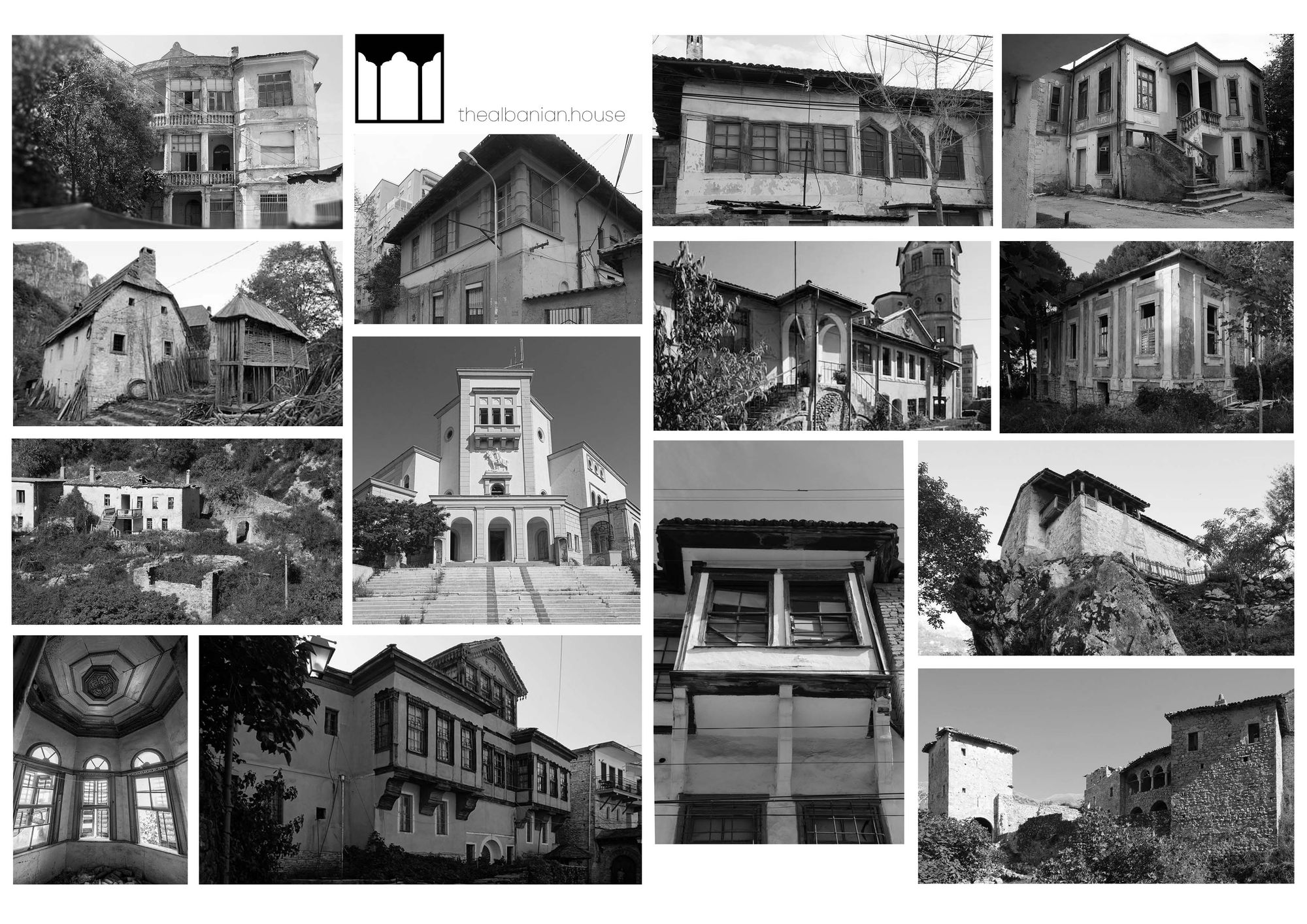

While researching preservingtirana.city, we discovered that, to a large extent, the type of building that was most at risk of being abandoned and left at the mercy of the passing of time, was the residential house. Based on this finding, we decided to create a similar platform in order to document this specific architectural category but across a considerably wider geographical area, specifically throughout Albania, including both rural and urban familial dwellings, from north to south. (Fig. 3)

The platform was given the name thealbanian.house and, just like preservingtirana.city, it is an interactive website that merges the use of open source platforms with participatory architecture in order to create an archive of the Albanian home as one of the most important categories of buildings that testify to the economic, social, and cultural development of the country at different historical periods, being so intimately connected to everyday life. (Fig. 4)

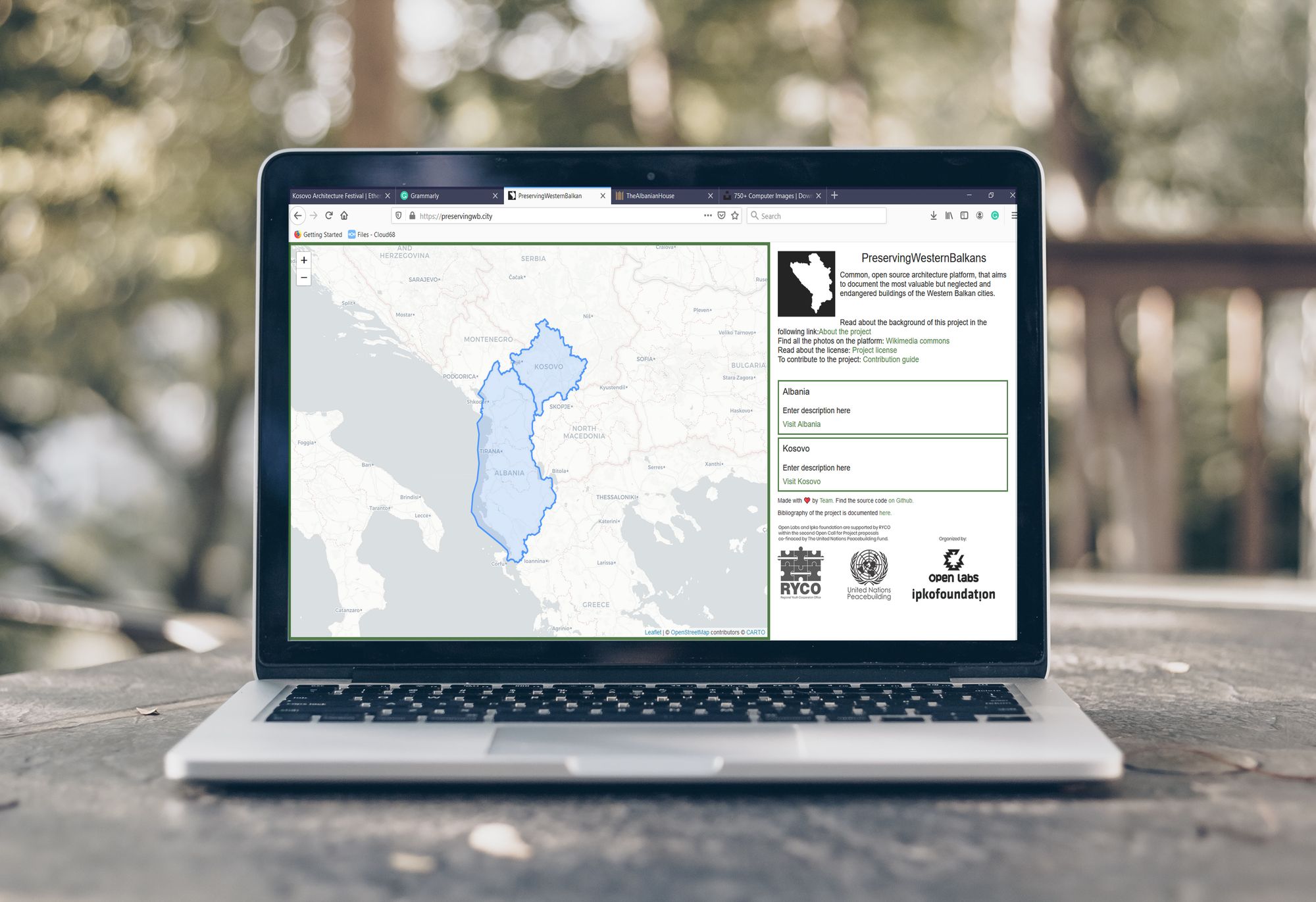

Gradually, the conjoined themes of “undesirability”, “abandonment”, and “vulnerability” started to resonate and reverberate outside of Albania, specifically in the capital of neighboring Kosovo, Pristina, and its urban context which, of course, has a host of other specific issues as a result of its unique historical and political development. The project that ensued was preservingpristina.city, under the umbrella of preservingwb.city, a platform encompassing the entire Western Balkans region, where preservingtirana.city served as a pilot project. (Fig. 5)

This organic continuation and expansion of the original project demonstrated the need for this type of documentation across the region and, obviously, the many similarities between different countries in the region in terms of architectural and urban development.

This type of documentation is important because by (re)turning the community’s attention to the very real values embodied in architectural works that are otherwise blighted by “undesirability”, “abandonment”, and “vulnerability”, not only protects them from forgetfulness but also constitutes a first and very important step for their future preservation. In addition, this type of documentation creates the necessary conditions and opportunities for opening new discursive paths in terms of how this past may be used in different future scenarios. The possible future scenarios that we see for these buildings involve, first of all, their reevaluation and renaming not only or no longer as “undesirable buildings” but, rather, as buildings that are fundamental to the city’s identity, through innovative ideas for their re-use and revitalization.

As the activist and journalist Jane Jacobs remarks in The Death and Life of Great American Cities: “Old ideas often use new buildings, but new ideas must use old buildings.”[5]

[1] Albana Rexhepaj, Përpjekja (Shqiptarët dhe arkitektura), nr. 34–35, Tiranё: Qendra “Përpjekja”, 2015–16.

[2] Ermir Hoxha, Arkitektura shqiptare e shek. XX, Tiranë: West Print, 2015.

[3] Melanie Van Der Horn, Indinspensable Eyesores: An Anthropology of Undesired Buildings, New York dhe Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2009.

[4] Italo Calvino, Le città invisibili, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974, pp. 30–1.

[5] Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, New York: Modern Library, 2011.

Notes:

This article was published on ‘Art Studies Journal’, Department of Art Studies, Institute of Cultural Anthropology and the Study of Art, Academy of Albanian Studies*

Thanks to Jonida Gashi for the article translation in english.